We all know race engines means high tech and expensive. Because these engines are only produced in small volume and usually working in high load/high stress circumstances, they usually uses some technologies that are not available in massively produced passenger cars.

One interesting fact is, because the race engine has higher assembly precision standards, there is less energy loss due to frictions between internal moving parts. Therefore, some race engines do have better fuel efficiency when comparing to a similar massively produced passenger car engine.

But some good stuff in race engines may act reversely in cars that are designed for daily driving. One example is the coating of the cylinder liners. Let’s take the 3.8L turbo V8 engine which is used in the latest Maserati Quattroporte GTS.

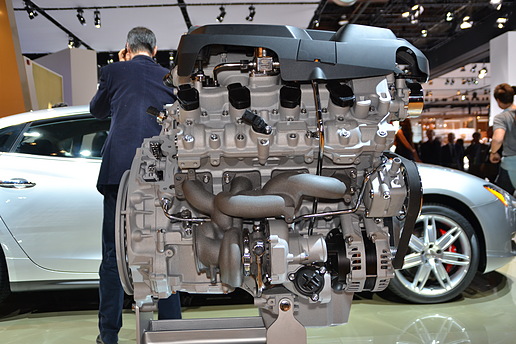

That 3.8L V8 engine is built by Ferrari. The engine block is made using Aluminum, with wet thin steel cylinder liners (“wet” means the coolant can touch the outer side of the liners directly). This is a typical Ferrari engine design. But the problem is: Ferrari applies a Nikasil coating to the cylinder liners. Below is the side view of the Ferrari-developed 3.8L V8 turbo engine.

Nikasil coating is ultra-hard, friction-reducing and also saves weight for the liners (because one can use thinner metal materials because of the extra strength of the coating), and this is critical for high performance purpose engines. But this kind of coating has an unavoidable shortcoming: it is very vulnerable to the sulfur content in the gasoline.

Sulfur in the gasoline, combines with some ambient molecules, and it forms sulfuric acid, which corrodes the Nikasil coating gradually. When the Nikasil material starts to fail, piston rings will score the cylinder walls and causing reduced compression ratio, which also lowers the engine output. After this process has reached to some extent, besides feeling the reduced power you will also find it takes longer and longer to crank the engine to start in the morning. In the end, when the Nikasil coating completely fails, there will be virtually no compression to make your engine start.

In 1990s there were some German auto makers extensively using Nikasil to coat their engine cylinder walls. But they soon faced huge failure rate in markets outside of Europe, such as in US. The reason why they did not realize this during the design and test phases is because, Europe market has the lowest sulfur level in gasoline (less than 10ppm); while gasoline sold in other places of the world contains much higher sulfur. For example currently in US, EPA allows fuel refiners to produce gasoline with a range of sulfur levels, as long as their annual corporate average does not exceed 30ppm; for an individual batch, it can contain as much as 80ppm of sulfur.

For the Maserati Quattroporte GTS, if it is used for daily driving/commuting purpose, I believe owners will start to complain engine issues once they have accumulated enough miles on their Quattroportes.

Some may ask this question: why so many exotic sports cars and racing cars are using Nikasil coating?

The answer is simple: statistically speaking most of the exotic sports cars (Ferraris, Lamborghinis etc.,) won’t see too many miles because their owners are not using it to deliver fast food, or drive it for 12 hours every day. Most of such cars I have seen for sale are only driven several thousands of (or even hundreds of) miles per year, it is very unlikely for this issue to develop to the extent that is noticeable to its owner. For race cars, professional racing team has the financial budget to replace an engine for every 600 miles; obviously reliability is not their first priority.

Recent Comments